by John Fawaz

“What next?”

It’s the question asked by every professional athlete. At some point, everybody hangs ‘em up. Only then do they begin to consider the next chapter of their lives.

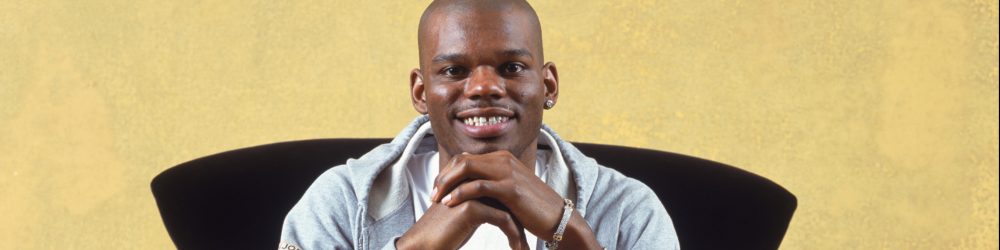

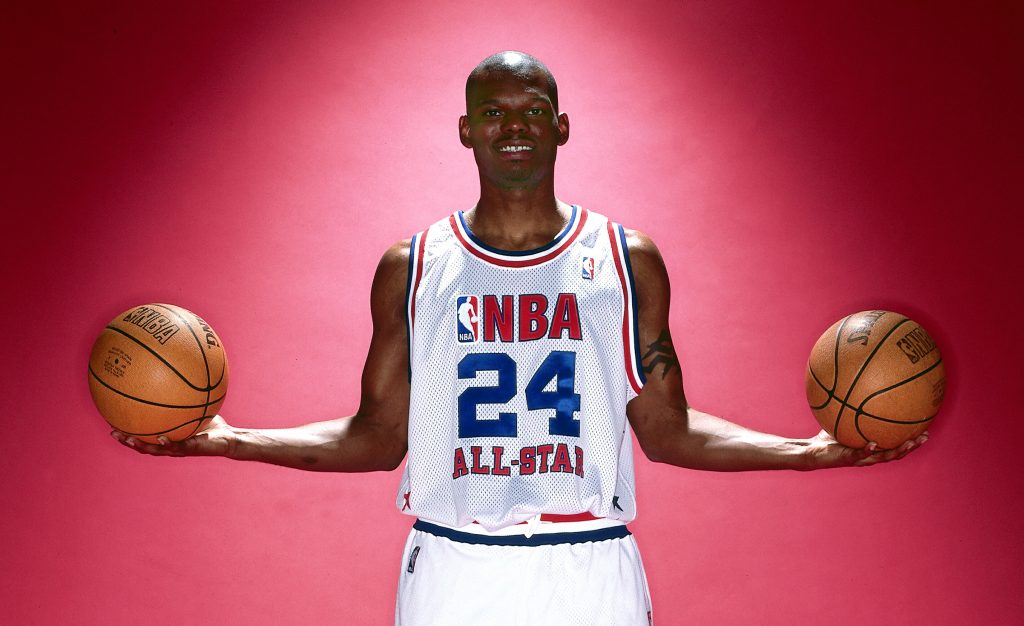

Jamal Mashburn had that all worked out well before he retired from the NBA in 2006. You can learn a lot riding the subway.

“I got a chance to see the train transition from blue collar, working class to white collar, business suits,” Mashburn says, remembering his days riding from his Harlem home to a Catholic school in Manhattan. “I had aspirations to find out what was in the briefcases and do that.

“Riding that train, I had to figure out how to carry that briefcase.”

Mission accomplished, although in this era the briefcase has been replaced by a smartphone. Mashburn, who turned 46 in November, has amassed a business empire that includes restaurants, auto dealerships, a marketing agency, real estate development, juice franchises and tech investments, just to name a few. He is living the life he envisioned as a youngster, well before his NBA dreams.

“I looked at basketball as a way to meet a lot of people and get an education so I can carry that briefcase,” Mashburn says. “Those train rides gave me a lot of inspiration.”

Basketball and business were “parallel dreams” and every step of his journey had to further both ambitions. Never stop learning on the court, in the classroom and, most of all, in everyday life. Never stop aspiring.

“If you’re the best player on your team, you need to find a new team,” Mashburn says. “I’m a true believer in that you grow from others’ experiences as well. Always in basketball and always in business, I’ve transitioned well because I am a constant learner.”

The subway introduced Mashburn to a different environment, but back home in Harlem he was like any other kid, playing sports with his friends. This being New York, playground basketball ruled. But Mashburn was a pudgy youngster and not the most skilled player. The only way to change that was to practice. For that he needed a ball, and the neighborhood had just one. Seriously.

“I never owned a basketball. When I was growing up in the projects in Harlem, it was more like a community basketball,” Mashburn says. “He who left last had to secure the basketball. Lights out at ten, I would always be the kid out there playing by myself.

“That’s how I honed my skills, how to bargain. I don’t think I ever gave up the basketball. I was the guy who was out there first and the one who stayed latest. I had to figure out a mechanism to keep that tool.”

By his teen years, Mashburn showed promise, though his weight remained an issue. Big for his age, he regularly played against older kids. He realized that this sport was also a business (“I had value because I could play the game”) and he asked a lot of questions. He wanted to absorb as much information as possible. Nothing has changed.

His high school years were centered on basketball. Even then, with AAU and summer camps, there wasn’t much of an offseason. But his education continued, both in a traditional and nontraditional sense. Though his parents separated when he was 11, Mashburn’s father lived nearby and they saw each other almost every day, while his mother, Helen, exposed him to a different side of New York with trips to museums, restaurants and other cultural activities. As he said, she gave him what he needed, not necessarily what he wanted.

Maybe the biggest lessons came when she took him to collect rents as part of her bookkeeping job. They discussed her work (“my mother taught me debits and credits”) and his future. She wanted Jamal to be able to tell her anything, even things she didn’t want to hear. Don’t count on a career in the NBA, she cautioned. Get your college degree. Be ready to do something else. She needn’t have worried.

“My mother always said, ‘Have something to fall back on,” Mashburn says. “I pushed back. ‘I don’t want to fall back on something. I want to fall forward.’”

More importantly, he had no illusions about the dreams of sports glory. His father, Bobby, had been a boxer. His decade in the ring included a fight at Madison Square Garden and bouts against Larry Holmes and Ken Norton, two future heavyweight champions.

“I saw my father, and the other side of being a professional athlete and not having any fame or riches,” Mashburn says. “He never got a chance to live out his dream. I wanted to take a different direction.”

By his senior season of high school, Mashburn had dropped the pounds and became one of the city’s top players, a small forward who could knock down outside shots. College coaches, assuming that he would be leaving early for the NBA, mostly talked basketball during their recruiting pitches. Mashburn’s priorities were different. He wanted a college that was the right fit. Yes, he might leave early if it made economic sense, but he wanted a school that would help him achieve his ultimate goals. As he says, it was all part of “investing internally by making the right decisions and developing a business plan” for life, a process he began at age 13.

“I had to figure out what college I wanted to go to,” Mashburn says. “Did it match up with what I wanted to accomplish?

“A lot of coaches who were recruiting me didn’t take me seriously.”

One coach who did take Mashburn seriously was Rick Pitino, who coached at Providence before taking over the Knicks in 1987. The two had developed a rapport during summer hoops camps in New York. Before Mashburn’s senior year of high school, Pitino left the Knicks to take over at Kentucky, which was quite a distance — literally and figuratively — from Harlem. The Wildcats were on probation, so if Mashburn followed Pitino, he wouldn’t be able to play in the NCAA Tournament his first year. A program in the Atlantic Coast Conference or Big East seemed the most likely landing spot. But coach and player clicked, and Mashburn signed with Kentucky.

“He always allowed me to use my IQ, either on the court or off it,” says Mashburn. “He had an open-door policy that I used, more than others, to go in and express concepts and ideas. And he promised he would tell me when it was time to leave [for the NBA].”

Mashburn compiled a solid freshman season (1990-91) at Kentucky and then emerged as one of the top players in the nation in his sophomore year. He led the Wildcats to the Final Four, and nearly to the 1992 NCAA Championship Game by scoring 28 points in an NCAA Semifinal Game. But, in one of the greatest college games ever, Duke dashed Kentucky’s hopes when Christian Laettner hit a game winner at the buzzer in overtime.

After that loss, Mashburn was invited to California as part of a group of college all-stars assembled to play against the original Dream Team. When he returned from the scrimmages, Pitino called him into his office and told him it was time.

“He said, ‘This is going to be your last year here,’” Mashburn recalls.

As a junior, Mashburn was the Southeastern Conference Player of the Year, and he led the Wildcats to the NCAA Final Four before another overtime loss ended their title hopes. Mashburn, who had already announced his intention to turn pro, returned to the coach’s office at season’s end.

“Remember how you want to carry the briefcase?” Pitino asked. “You’re going to sit down and hire an agent and hire a business manager.”

So began the interview process. First, Mashburn chose an agent after speaking with several candidates. Then it was time to select a business manager, but that proved more difficult. They offered him investment ideas and portfolio management. In other words, a life of leisure after his playing days ended.

“What happens with athletes sometimes is that people don’t think you have a vision beyond playing,” Mashburn says, recalling the process. “Only one [Rick Avare] listened to my vision of carrying the briefcase.

“I told him, ‘I want to step into a live, active business after I play in the NBA. I need you to teach me everything in finance and accounting that you know.’ Eventually he morphed into my business partner.”

Mashburn entered the 1993 NBA Draft as one of the top prospects. In those days, players who stood 6-8 and could shoot threes were rare. Dallas selected him fourth overall, after Chris Webber, Shawn Bradley and Penny Hardaway.

Mashburn averaged 19.2 points per game in 1993-94 to lead all first-year players and he finished third (behind Webber and Hardaway) in the balloting for the NBA Rookie of the Year Award. The next season, Jason Kidd joined the Mavericks, combining with Mashburn and Jim Jackson to form the “Three Js.” Dallas, which had won just 24 games combined in the previous two seasons, improved to 36-46 in 1994-95. Mashburn averaged 24.1 points per game to rank fifth in the NBA. The Mavericks future looked bright.

At the same time, Mashburn and Avare began planning for life “once the ball stopped bouncing,” as Mashburn puts it. He connected with Chris Sullivan, one of the founders of Outback Steakhouse, and used some of his shoe contract money to purchase a franchise. He would go on to acquire 38 Outback Steakhouses before selling his interest in 2018.

Mashburn describes that initial investment as the catalyst for the ventures that followed. During the next 20 years, he bought and sold fast food franchises and a printing plant, started and sold a venture capital firm, and invested in real estate and tech companies. Mashburn currently owns 90 Papa John’s franchises, three locations of a fitness company and five auto dealerships (he says he has learned the most from those businesses). He joined Jonathan Sackett to open the Mashburn Sackett advertising agency, and he is beginning to develop hotels.

While his financial endeavors flourished, he experienced ups and downs on the court. A knee injury limited Mashburn to 18 games in 1995-96 while the Three Js clashed. By 1997, all three were out of Dallas, with Mashburn going to Miami in a midseason trade.

Mashburn would play three and a half seasons (1997-2000) with the Heat and four with the Hornets (2000-02 in Charlotte and 2002-04 in New Orleans). He averaged 21.6 points per game in 2002-03 to earn All-NBA Third Team honors. But his knee, worn down by repetitive injuries, limited him to 19 games in 2003-04 and finally forced his retirement in 2006.

“It eventually stops. What do you do now?” says Mashburn, who averaged 19.1 points per game in 11 NBA seasons. “What did you learn from the experience that you can use in the new life? What don’t you need that you can get rid of?”

Mashburn applied his basketball lessons to his new life. Preparation, preparation, preparation. Don’t let the ball dribble you, you dribble the ball. As you become better as a basketball player, you become better at moving the ball.

“I’m very selective on things that I do, and I am very methodical in my approach. Very parallel in how I played,” Mashburn says. “To me, that was the secret sauce. Prepare and the game takes care of itself. Got to have good people and teammates around you. I prefer myself to be a teammate, to let other people flourish.

“I like to be around people who have lived their dream and can also express it and teach it.”

Though Mashburn made a bid for the New Orleans Hornets (now Pelicans) in 2012, owning an NBA franchise is likely not in his future. The value of franchises has soared to the point that it doesn’t make business sense (“the return is all in appreciation”). But he remains connected to the NBA and the game. Players seek him out, and he is happy to help.

“I do get approached quite a bit for information,” Mashburn says. “They ask how I did what I did and how do I continue to do it. It’s a lot of fun to share my stories.”

“When I was coming into the NBA, the League and Players Association would bring in guys who made mistakes. They would preach about ‘Don’t do this.’ I always wanted to hear the story about the guys who made the successful transition.”

For the veteran players who are pondering retirement, Mashburn reminds them that they have the tools. They just need to be repurposed.

“There’s a lot of work to be done, like the work they did to get to the NBA, but it’s more of a lifestyle change,” he says.

Meanwhile, his son, Jamal Jr., is a junior in high school and one of the top guards in the nation. Like his dad, he is eyeing a parallel track — he wants to play in the NBA and be an attorney. Soon he will have to pick a college. Those recruiters better do their homework. The Mashburns have a lot of questions.