by NANCY LIEBERMAN

It’s a great time to be a female in the game of basketball. Opportunities are all around us, and the WNBA is on the verge of major growth. The creation of the WNBA inspired hope – a hope that women can not only play basketball at the highest level, but can earn a good living doing so.

I have experienced this dynamic first-hand. I have witnessed how the game of basketball has become bigger, better and stronger for women. More importantly, I acknowledge the great opportunities still ahead of us. In order to take steps toward that brighter future, it’s time to take a step back and really understand the facts and expectations for the future.

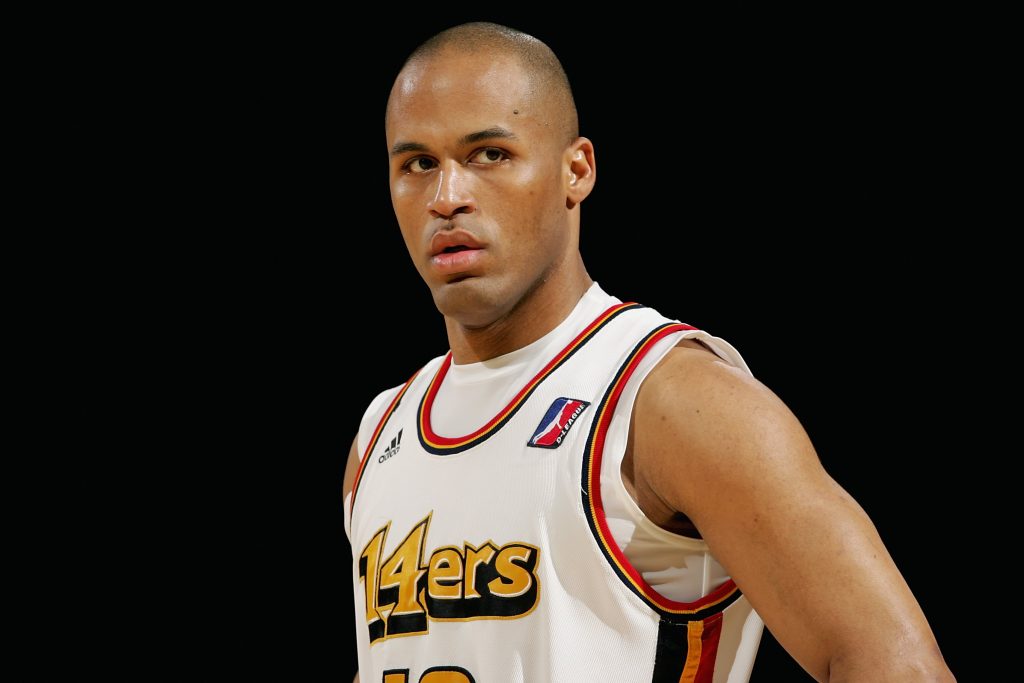

First, we can’t continue to believe the myth that men are holding women back – it’s just not true. I was hired by men for every major job I’ve had. I was hired by men from the USBL. I was hired by men to work at Fox and ESPN. I was hired by men to be the first female head coach in NBA G League history. I was hired by men to be the assistant coach of the Sacramento Kings. Ice Cube took my career to the next level, making me the first female head coach in any men’s professional league when I joined the BIG3. I can go down a long list of men who wanted to help me succeed.

Furthermore, there is a healthy respect from male players toward women who play the game. I have never had an issue with men in the league respecting me, especially the players. It’s the outside world that says, “Wait, there’s a girl on the court.” They were the ones who didn’t think it was normal because they hadn’t built the camaraderie we had as players.

For these reasons, we cannot blame the men of the game, as they will only continue to push us toward a better future. I have so much respect for Adam Silver, who so badly wants the WNBA to succeed. It’s men like him who will help put us in the best positions to prosper.

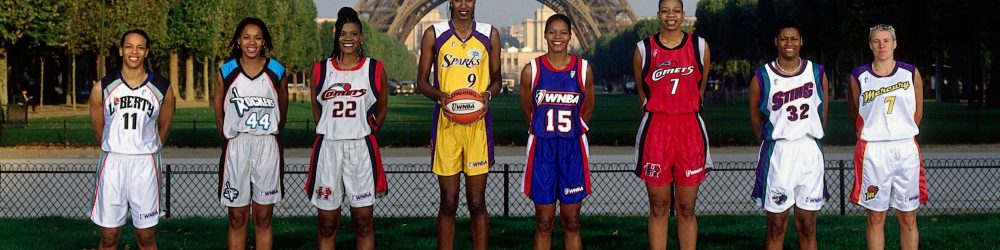

In addition, we must look at the WNBA as a business through an unemotional and unbiased lens. If you want an accurate perspective, go back to when the NBA fi rst started in 1946. Players were making $10,000 when the league began. When I started in the WNBA in ’97, I was making $40,000, and the top salary was $50,000. The NBA helped put us in the spotlight instantaneously, but the onus is still on us. It’s not our birthright to have a WNBA. It’s not Skittles. Everybody doesn’t get one. It’s business. We still have to sell tickets and fill the stands, and sometimes that takes sacrifice.

We women are getting the opportunities to coach, learn, network and share, but we have to grind. In the name of gender equity, it’s nice to be thought of,

but we still have to earn the right to be there and have to create the necessary relationships. The women currently in the league have busted their behinds to get there – nothing was handed to them. That’s what it takes to be a pioneer.

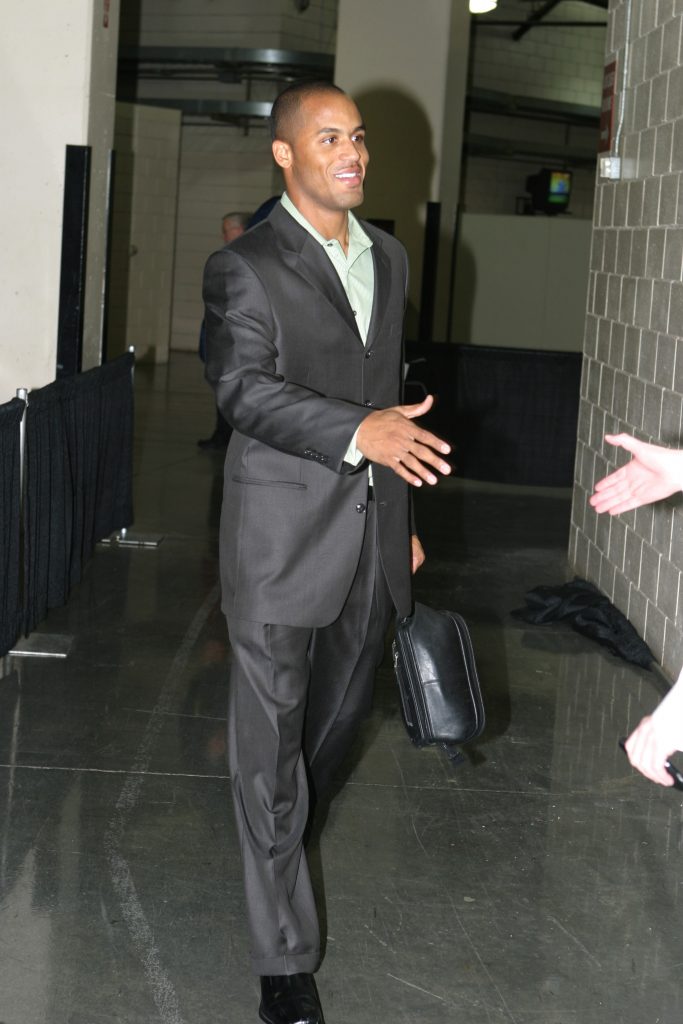

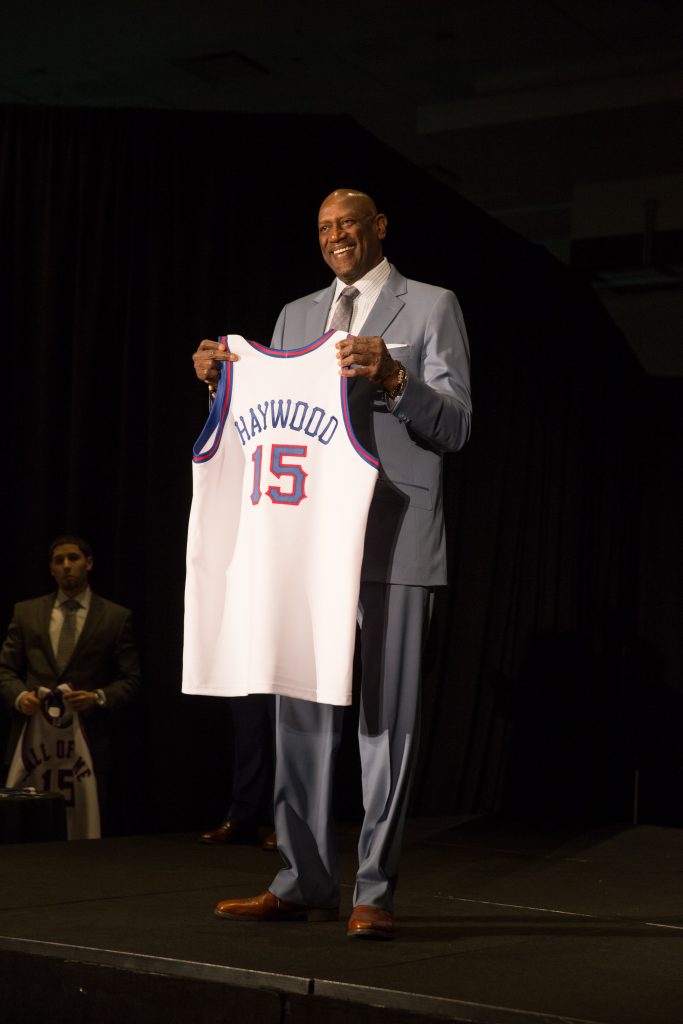

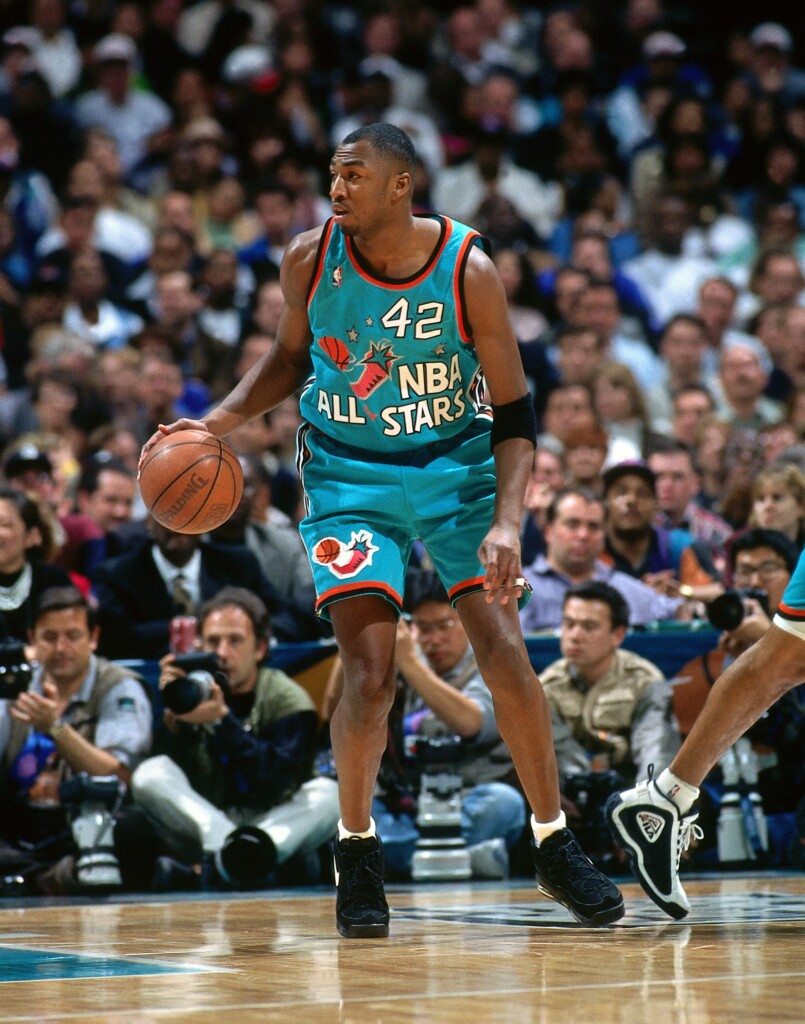

(Photo by Rocky Widner/NBAE via Getty Images)

I, along with many other women from my era, have made sacrifices for what we have today. I’m not mad or jealous that I didn’t make the money that today’s players are making. I understood what it took and what I had to sacrifice to create a better future for the game. For five years I went to the NBA summer league on my own nickel. I invested in myself because I knew I had to be around the people who would give me the opportunity one day. If I didn’t believe in myself, why should anyone else?

Every player in the WNBA, past and present, is a role model, a barrier-breaker, a pioneer and a trailblazer. To hold that responsibility, I will ask this: are you willing to make sacrifices today so others can thrive in the future?

I feel a tremendous amount of humility and gratitude to have done something right for a game that changed my life on so many levels. What my greatest role model and friend Muhammad Ali taught me when I was younger was that there are two people in life: givers and takers. He inspired me to be a giver, and I encourage the rest of the young women currently playing basketball to be givers and make sacrifices to better the future of the game.

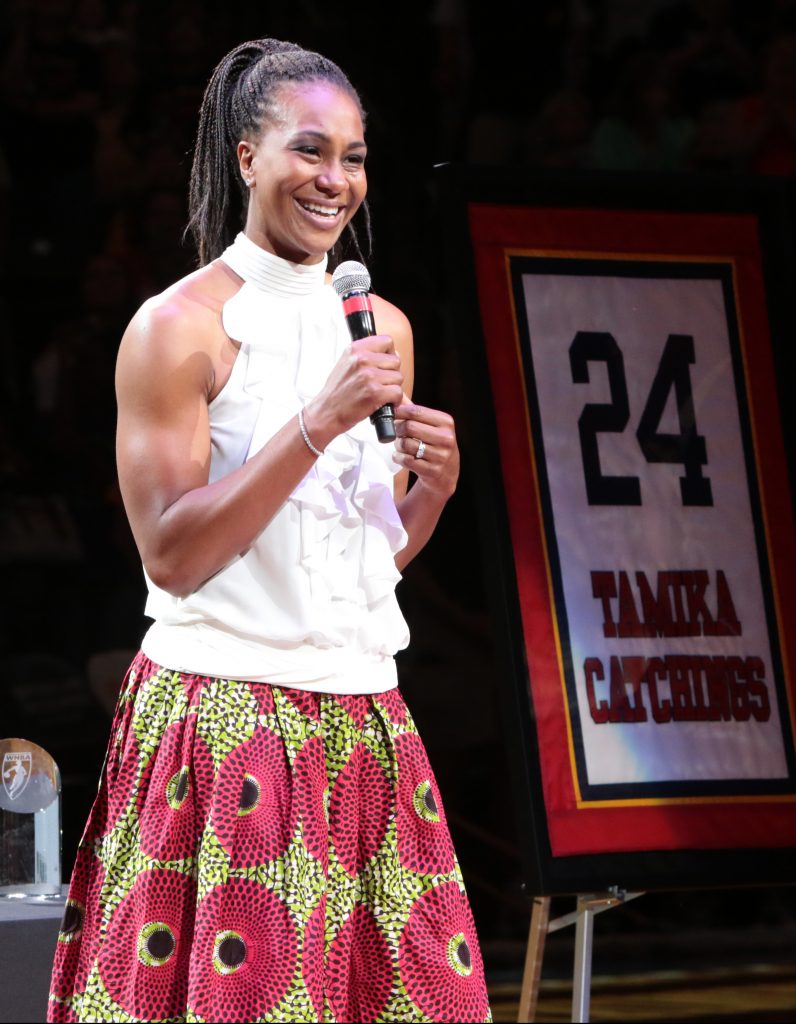

Dallas, Texas. (Photo by Layne Murdoch/NBAE via Getty Images)