by BEN LADNER

Before the NBA’s popularity exploded to a point of national interest, before player contracts exceeded those of corporate executives, before stars could

devote off seasons exclusively to training and vacationing, Dave Bing spent his summers working at a bank.

Coming out of college at age 22 and in search of a home, Bing had applied for a mortgage on a house, but was turned down after the National Bank of Detroit deemed his lack of credit history too risky for a mortgage. The following year, after Bing won Rookie of the Year and established himself as the best player on the Detroit Pistons, Bing had secured a mortgage from a different bank altogether. The first bank, however, didn’t forget about Bing, and reached out to apologize – and offer him a job.

“The relationship wasn’t sour,” Bing said, “because I was big enough, strong enough to say, ‘Look, they made a mistake. They now want to employ me.’ And I needed a job, because back then, obviously, we weren’t making a lot of money.”

Bing worked at the National Bank of Detroit for seven off seasons, and while he went on to play 12 seasons in the NBA, those summer jobs helped prepare him for what was in store once his basketball career ended. While many retired athletes dabble in business ventures via investments or partnership, Bing had dreamt of starting and operating a business long before he entered the NBA. His father, Hasker, ran his own bricklaying company in Washington D.C., and while Bing vowed never to work in that industry after Hasker suffered a life-threatening injury, he long hoped to emulate his father as a businessman. “I always wanted to be an entrepreneur,” Bing said. “I saw what [my father] did, what he accomplished. I saw the struggles that he had.”

In spite of his own obstacles – namely his diminutive stature and impaired left eye – Bing excelled in both basketball and baseball at Spingarn High School in Washington, D.C., the same school that produced Elgin Baylor. After a growth spurt and an illustrious high school career, he earned a basketball scholarship at Syracuse, where he blossomed into one of the most dynamic guards in college basketball. He went on to lead the league in scoring and earn two First Team All-NBA nods in an era that featured Walt Frazier, Earl Monroe, Oscar Robertson, and Jerry West. Though his Pistons never ventured far into the postseason, the success they did have was driven mostly by Bing’s scoring and playmaking.

In 1980, two years after he retired from the NBA, he started Bing Steel, which supplied steel to automotive companies out of Detroit. In the two years between retirement and founding the company, Bing devoted himself to learning the steel industry, taking classes and studying other companies to prepare himself for this new venture. Bing Steel struggled in its first year, and with just four people on staff, took time to find its footing in the industrial world. By the company’s second year, however, it took on General Motors as its main client and turned a $4.2 million profit. In 1984 Bing was named the National Minority Small Business Person of the Year by President Ronald Reagan, and by 2008 the company had sold $300 million of materials, opened five different plants in Detroit, and employed over 1300 people – most of them African American. “I was an African-American entrepreneur,” Bing said. “I felt it was important to make sure I hired as many African-Americans from the city of Detroit as I could.”

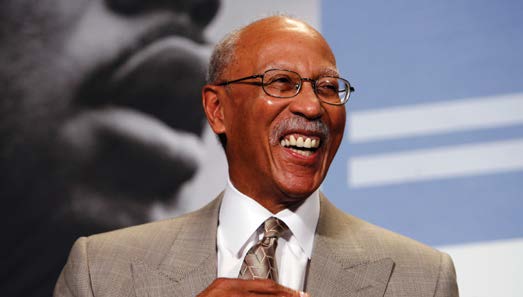

Bing’s devotion to the black community became the basis for much of what he did after his NBA career, both in business and in politics. In a city whose

population is over 80 percent black, Bing felt an obligation as a successful and prominent member of the community to serve and represent its people. When the city’s mayor, Kwame Kilpatrick, was removed from office in 2008 for committing perjury and obstruction of justice, several prominent members of Detroit’s business community – including Roger Penske and Tony Earley – identified Bing as Kilpatrick’s logical successor – at least for the remainder of the term. “They basically asked me to run for it,” Bing said. “It’s not something I [sought] out.” He deliberated for a few months before deciding to run among a field of 15 candidates – and won.

Dave Bing and Isiah Thomas speak at the half time jersey retirement ceremony for Chauncey Billups during the game against the Denver Nuggets on February 10, 2016 in Auburn Hills, Michigan. (Photo by Allen Einstein/

NBAE via Getty Images)

After completing Kilpatrick’s term, Bing was reelected in 2009. The latter portion of his tenure proved trying for Bing and his administration, and much of their work involved rectifying the mistakes of previous administrations. Still, in 2013, four years into Bing’s second term, Detroit fi led for bankruptcy – the largest city in U.S. history to do so. Despite an unceremonious ending, Bing learned and grew from what he called “the toughest four years of [his] life,” and maintains that he would do it all over again if given the choice. He also believes that his experience as an entrepreneur and NBA team captain gave him the necessary skills and background for a political career. As a player, Bing knew not only his own strengths and weaknesses, but those of his teammates, and sought to mesh complementary skills with one another. In both the business and political realms, he surrounded himself with people who possessed expertise in areas he didn’t.

“Picking the right people to be part of my team was very, very important,” Bing said. “It’s a people business, and you’ve got to make sure you give people the respect and the dignity to let them do their job.”