by John Fawaz

Haywood v. NBA. 1971. For a time it seemed more like Spencer Haywood against the world.

Booed in every arena but his own in Seattle. Protests filed by numerous NBA teams, including one by a franchise that had tried to sign Haywood. Sued by the ABA. Injunctions served during warmups. The Cincinnati Royals kicked him out of the arena, and into the snow. Opposing players delivering elbows to Haywood’s jaw. And those were the polite objections.

“There were some serious threats,” Haywood says. “Booing was ‘nice.’ People would try to entice me to fight because if I punched somebody, the whole case would blow over.”

The controversy entered the realm of farce when Chicago, after losing to Seattle, demanded $600,000 for the diminution of the Bulls’ playoff chances and for the injury to All-Star Chet Walker. Imagine how much money the Bulls would have asked for if Haywood had actually checked into the game.

Haywood’s offense? He wanted to play in the NBA, and he didn’t want to wait until he was 22 years old, as the League required.

“The NBA was not accepting of the idea,” Haywood says, putting it mildly. “They said you have to wait two years [or] you can go play in Belgium.”

An unstoppable 6-foot-8 forward with a unique skill set, Haywood led the U.S. team to the gold medal at the 1968 Olympics at the age of 19, and then averaged 32 points and 22 rebounds per game in the 1968-69 season while playing for the University of Detroit. For Haywood, the youngest of 10 children of a single mother worn down from a lifetime working in the Mississippi cotton fields, college was a luxury he just couldn’t afford.

Haywood went to the ABA, which enacted a hardship exception in its bylaws that allowed its teams to sign players who hadn’t completed their college eligibility. Hysteria ensued. The end of civilization was near, so it was said, or at the very least the end of college athletics. All censure, of course, was couched in terms of concern for Haywood and other student-athletes.

The ABA proved to be no friend, either. After Haywood won the 1969-70 ABA MVP Award as a rookie, the Denver Rockets gave him a new contract worth $1.9 million. Or so they said.

“I signed it without legal counsel,” Haywood says. “I got a raise from $50,000 to $75,000, and they would put $10,000 a year into the stock market, and when I get to age 55, I start drawing from that money if it’s there.

“And the agreement inside the agreement said that I would have to be employed by the truck line that owned the Rockets until I was 70 years old.”

Haywood hired an agent (Al Ross), and when he and Ross tried to renegotiate a clearly unfair contract, the Rockets’ owner told them to get out (peppered with a racial slur). Play for Denver or don’t play at all because the NBA won’t touch you.

Enter Sam Schulman, a lawyer and the outspoken managing partner of the Seattle SuperSonics. NBA Commissioner J. Walter Kennedy warned Schulman to steer clear of Haywood. But he couldn’t. Schulman wound up signing Haywood in December of 1970.

“Sam said, ‘I will give you the same contract you signed in Denver, but all in cash,’” Haywood says. “I got money, and I can play. I will do whatever Sam wants.”

The courts agreed. U.S. District Judge Warren Ferguson issued a preliminary injunction allowing Haywood to play for the Sonics. The NBA appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld the injunction in a 7-2 decision on March 1, 1971. Fewer than two weeks later, Ferguson granted Haywood’s motion for a summary judgment declaring the NBA rule invalid because it violated antitrust law.

As Schulman said later, “It was a matter of principle. I couldn’t see any logical reason for keeping a man from making a living.”

And the sky did not fall. In the decades that followed, veteran players did not lose their jobs to younger, cheaper players. The opposite occurred, as the influx of talent allowed the NBA to expand. College basketball became bigger than ever. In the NBA, revenue soared. All those extra years created tremendous wealth for NBA players and, more importantly, gave them more control over their lives and careers. Haywood v. NBA ended a system that benefited everyone but the players.

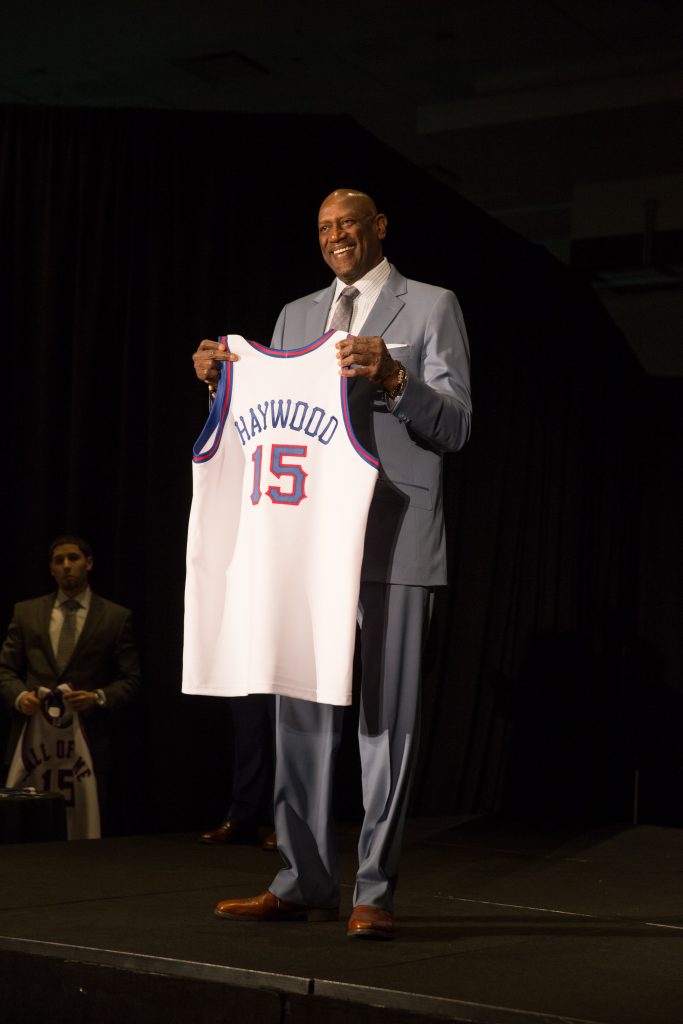

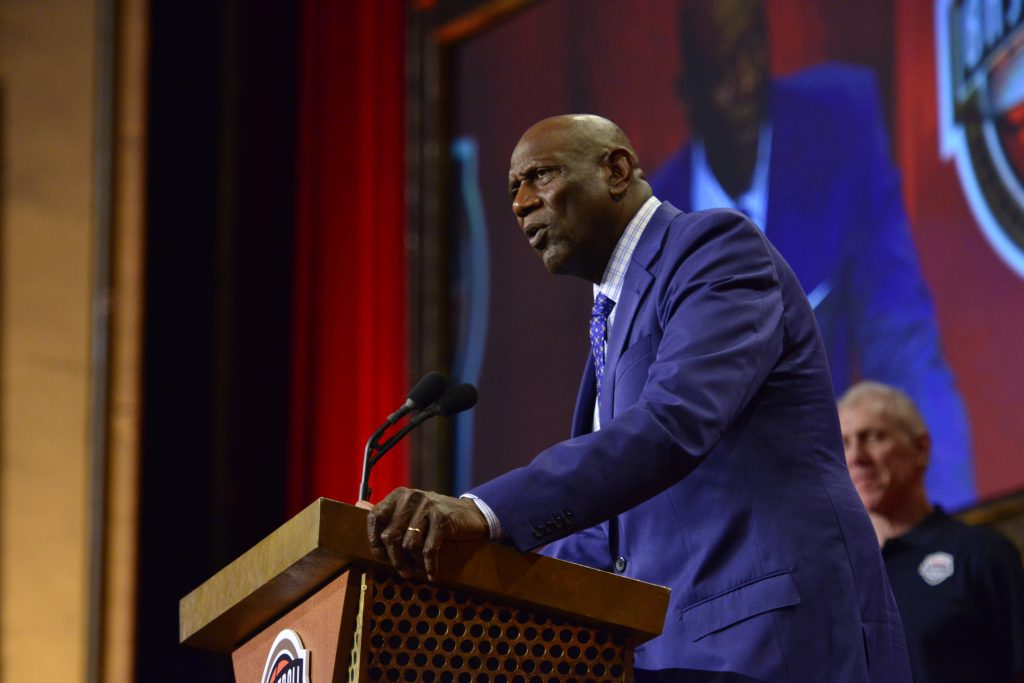

Haywood, who was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2015, is proud of his role as a Pioneer. But as he said in his induction speech, “Now remember guys, I had game. It’s not like I just did this Supreme Court thing. I had some serious game.”