by Sean Deveney

SPRINGFIELD, Mass. – It was a night for the overlooked, the underrated and the trailblazers whose contributions to the game have been too obscured by history.

The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame held its induction night this weekend and welcomed a field of new members that included center Vlade Divac, a pioneer of international basketball who was drafted from Yugoslavia by the Lakers in 1989 and went on to become the first player born and trained outside the U.S. to appear in 1,000 NBA games.

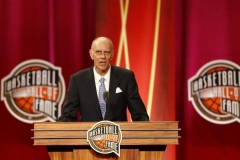

Divac opened the night with a speech that set the tone for the entire collection of inductees, speaking about his love for the game and emphasis the game puts on selflessness.

The group also included one of the WNBA’s first stars, Teresa Weatherspoon, as well as defensive stalwarts Sidney Moncrief and Bobby Jones, unique face-up center Jack Sikma, championship coach Bill Fitch and five-time NBA All-Star Paul Westphal.

“I believe love gives you the power to share your best self and to inspire others,” Divac said. “Love liberates you the power to make the impossible possible. Just like in life, when you play basketball you have to give in order to receive. On the court you are not just making moves alone, you are also giving your physical and mental strength, your passion, your talent, your trust in your teammates. This way, the power can multiply and the whole team wins. Basketball is the opposite of selfishness.”

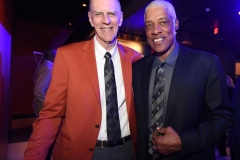

That resonated throughout Symphony Hall. Also inducted on Friday were Al Attles, who has been the face of the Warriors franchise for six decades—as a player, a coach and a franchise ambassador. Attles, chosen as a contributor, witnessed Golden State’s most recent dynasty, but was also on the floor as a point guard back when the team was based in Philadelphia in 1962, when Wilt Chamberlain scored 100 points in a game.

But, asked about the game earlier in the week, Attles was quick to point out that even Chamberlain’s dominating individual achievement had a team feel to it. “Well, I always remind people that we won the game, that’s the first thing,” Attles said. “The other thing is that Wilt tried to come out of the game. He did not want to score 100.”

Also inducted were Chuck Cooper, the first black player to be drafted by an NBA team; Carl Braun, a five-time NBA All-Star who played 13 seasons from 1947-62 and coached the Knicks briefly; the all-black Tennessee A&I teams (now Tennessee State) of 1957-59, which traveled to national tournaments, challenged segregation and were the first team to win three straight championships at any collegiate level; and the women’s teams of Wayland Baptist University (1948-82), who won 10 AAU championships and once won 131 consecutive games.

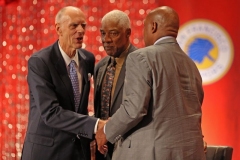

The honor was probably overdue for both Moncrief, who made five All-Star teams and won the first two NBA Defensive Player of the Year awards, and Sikma, who made seven All-Star teams and averaged 15.6 points with 9.8 rebounds. Sikma was also instrumental in bringing the 1979 NBA title to Seattle in his second NBA season.

But Sikma was best known for developing a step-back, face-up shot that became known as the “Sikma move.” It has regained popularity in the modern NBA, with fewer back-to-the-basket centers, but Sikma said it started mostly out of necessity—he grew 10 inches in his final two years of high school and arrived at tiny Illinois Wesleyan, as he described it, as a, “6-11, 195-pound specimen.”

Sikma recalled that, in his first Summer League game after being drafted by Lenny Wilkens and the Sonics in 1977, he had the misfortune of going against Moses Malone, who as already established as a star center. Because players can’t foul out in Summer League, Sikma said Malone wound up with 30-something points while Sikma had 10 fouls.

“The owner was there,” Sikma said, “and asked Lenny, ‘Is that our first-round draft pick?’”

The night was highlighted by the speech from Weatherspoon, whose passion for the game remains palpable even 15 years after her retirement. Weatherspoon won a gold medal with Team USA in 1988 and played overseas for 10 years before the advent of the WNBA. She created one of the great moments in league history when, playing for the New York Liberty in the 1999 Finals, she launched a buzzer-beater from beyond halfcourt that went in for a Game 2 win.

Speaking to her two brothers and three sisters seated nearby, Weatherspoon said, “I never had to look outside my family for my heroes. … I was well-protected, well-watched over and I hope that you know that everything about you, I watched. I took it from you, I took your perseverance, I took your consistency, I took your dedication, I took your determination, I took it and I ran with it. And I hope that I made you tremendously proud.

“We’ve gone through a lot together, we’ve done a lot together, we fought together. Tonight, we go in together.”

She went in, indeed, with a well-rounded group that finally got their due. It was a celebration of the hard-working stars, the players and coaches who often gave up the notoriety and big headlines to sacrifice for winning.

As Moncrief put it, “I take great pride being inducted into this Hall. But as I was trying to think of, what do you talk about? It’s not really about me. It’s not about a speech. It’s about the game of basketball. The game of basketball that has changed everyone’s life in this room.”