by Sam Smith

“I long to hear that you have declared an independency. And, by the way, in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands. Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.”

—— Abigail Adams’ letter and reminder to John Adams of the Continental Congress on eve of American Revolution, 1776.

It was certainly revolutionary in 1997 when the National Basketball Association committed to advancing the women’s game. Sure, there had been basketball leagues for women, and the college space was vibrant with famous programs like Immaculata and Delta State. Women played in the Olympics as an official sport in 1976 after the Title IX law in 1972, and many found participation outlets in Europe and Asia. But there seemed no sustainability in the United States, the birthplace of basketball, the land of the free and the home of the brave and where all men — and women — were supposedly created equal.

David Stern and the NBA were determined to finally remedy the great inequality with a commitment that today makes the Women’s National Basketball Association the most stable and successful women’s professional sports league in the United States. The fact that the change comes under the aegis of the National Basketball Association is both predictable and appropriate. As many will recall, it was the NBA that first introduced all-African-American starting lineups to professional sports along with African-American management and ownership, easily making it the most progressive sports league in the world.

“The WNBA has been a change agent,” agrees Carol Blazejowski, basketball Hall of Famer and former NBA official. “It’s changed a lot of societal views. It has become a platform for women to feel a sense of pride and upward mobility, and to feel that they can achieve bigger and better things in the sports community, to be viewed as athletes and not separated as women or men. It has allowed us as individuals who are very capable of playing the game of basketball to serve as role models, and to offer all we can to the sports landscape.”

“There have been some bumps, some successes and failures,” continues Blazejowski. “It’s still going to take some time and patience. Society always accepted the male athlete, and it was a struggle [to be accepted] when I played. But that stigma has changed and it’s a rite of passage now, understanding that opportunities in sports are as important to your daughter as much as to your son for so many reasons — the chance to earn a scholarship, boosting self-esteem, and everything else that comes with playing sports.”

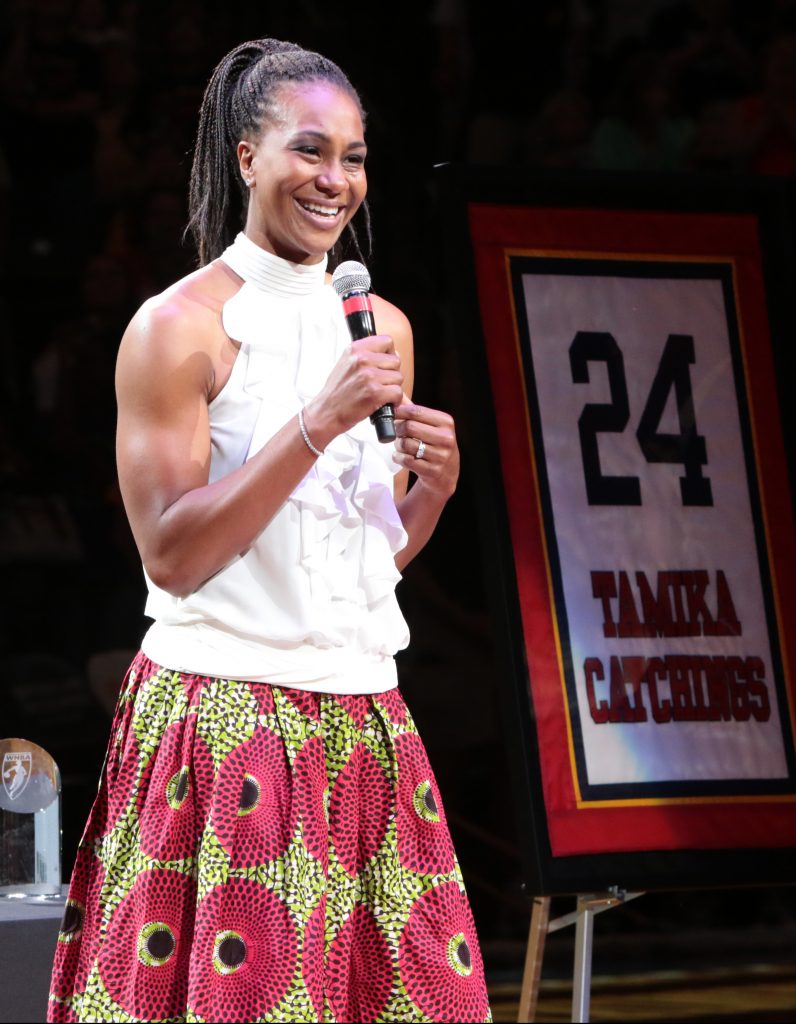

Tamika Catchings, a 15-year WNBA veteran who is now an Indiana Fever executive, figured she would follow her father and play in the NBA.

“Watching my father play (for four NBA teams) sparked interest in me being a professional basketball player and wanting to play in the NBA,” Catchings admitted. “We didn’t have the WNBA at that time. This is the generation that has grown up having an opportunity to be a part of something that is so much bigger than them, a league designed specifically for us. My goal was to be in the NBA, to follow in his footsteps. That really was the only thing I knew about. I didn’t even really understand the fact that women didn’t play. We had Annie Meyers and Lynette Woodard and the Harlem Globetrotters. I felt my dad did it, so I could do what my dad did.”

There are three- and four-sport athletes, and then there’s Ann Meyers, a seven-sport athlete in high school and the first female scholarship athlete at UCLA. Meyers actually did play in the NBA, albeit in preseason with the Indiana Pacers.

“I wouldn’t have done it if they were not serious,” Meyers says. “Yes, publicity was involved. But my whole intention in life was why was this any different? I like to think (I got close).”

Forget the glass ceiling; what needed to be shattered was the barrier to that glass backboard.

“We had actually commissioned a study some years earlier about what might be possible with respect to women’s basketball,” Stern said in an interview for the Retired Players’ Association. “I thought the time to do it would be in 1992 coming out of the Olympics, especially if the Americans won the gold. But they didn’t. They finished third and got bronze and it sort of went on the back burner.”

“Val Ackerman was working in our office and was a fiery advocate, as was Carol Blazejowski, and gradually (with Adam Silver) we began to develop a plan and we said, ‘OK, we could do this. We’ll do it coming out of the Olympics in ’96.”

Thanks to advocates like Ackerman and Blazejowski, the setback didn’t stop the birth of the new league.

“Val was totally intent on making it a dignified and authentic basketball experience,” Stern recalled. “The only thing I remember putting my foot down on was the ball. We agreed generally it would be smaller, but went back and forth on the color. I said if you never want to sell a WNBA ball, make it the same color as the NBA ball. We went with the oatmeal and orange, which has become a symbol of the league.”

Though the league is still not where it needs to be economically, there is no denying the quality of play is far better than anywhere in the world. It’s difficult to watch a WNBA game and then wonder why NBA players don’t consistently compete as intensely.

“Watching it is quite extraordinary,” says Stern, who still is active on several major U.S. boards and business ventures. “I remember when we started off and said this is the best women’s basketball in the world. But I would say the game is a factor of three times better.”

“We didn’t even know that some of these women existed because they were playing in countries you didn’t even know had basketball,” Stern added. “And so as it continues to grow, there will be increased revenues, salaries will be increased and from outside I would love to see these salaries and the revenue supporting a salary structure that allows WNBA players to play only for their team and not have to go to a foreign country to earn a maximum amount of money. But they only go there to earn that because they are WNBA players. They get their fame, reputation and celebrity from playing in the WNBA.”

WNBA players make about 20 percent of the NBA minimum salary in a league, of course, that generates substantially less revenue. Almost two thirds of WNBA players play during the winter outside the United States. It makes for a long year and creates heightened risk of injury. Seattle Storm star and league MVP Breanna Stewart suffered a torn achilles in Russia last April just before the start of the 2019 WNBA season. There are no one-and-dones as there is a four-year college rule for eligibility with a maximum salary slightly above $100,000 with some bonuses. WNBA players opted out of their collective bargaining agreement to negotiate additional economic terms after the 2019 season.

“The reality is people misconstrue this message,” she says. “It’s not about making the exact same amount of money NBA players make, or men make in general. We simply need to open people’s eyes to the fact we spend more than half of the year thousands of miles away and we don’t want to do that. We want to be able to play in our home country, in front of our friends, in front of our family and fans and be able to make a salary that will allow us to sustain an offseason. The reality for a lot of women is it would make sense to not play in the WNBA and just have the summer off and play overseas. But then we completely eliminate the idea of having a league here if all the best players aren’t playing in it. So we have to fight and give our all and our best to try to grow this league and stay committed to what Nancy Lieberman and Carol Blazejowski and all the players who came before us did and not let that die. They worked so hard for this thing to get going. We all love this game of basketball and we would be doing them, and honestly us, a disservice.”

Comparatively speaking, the WNBA is in its infancy. Twenty-two years into the NBA, boxing and track were still more popular and lucrative sports.

“It’s not going anyplace. It’s a smaller league and an unusual season. But as the game improved we learned a few things and that it isn’t just about mom and daughter. It is about dad and daughter and dad and son and mom and son going to enjoy a good basketball game. I’m not going to say the WNBA would have had an easy time without the NBA support because that’s not so. So it is something about which I am very proud. I think we did the right thing and we made the choices we had to make. In retrospect some might not have been the best choices, but they were the best choices made with a purpose and desire to provide a place for women to go after they finished college to move onto the next level of a great sport.”

“Now kids are going to NBA games and seeing female referees, female executives, and they will grow up thinking it was always that way, but it wasn’t,” says Stern. “We came from a more humble place. If you want to engage the world in a single conversation, sports is the way to catalyze that conversation.”

The WNBA has come a long way, and has a long way to go, but they’ve got game.