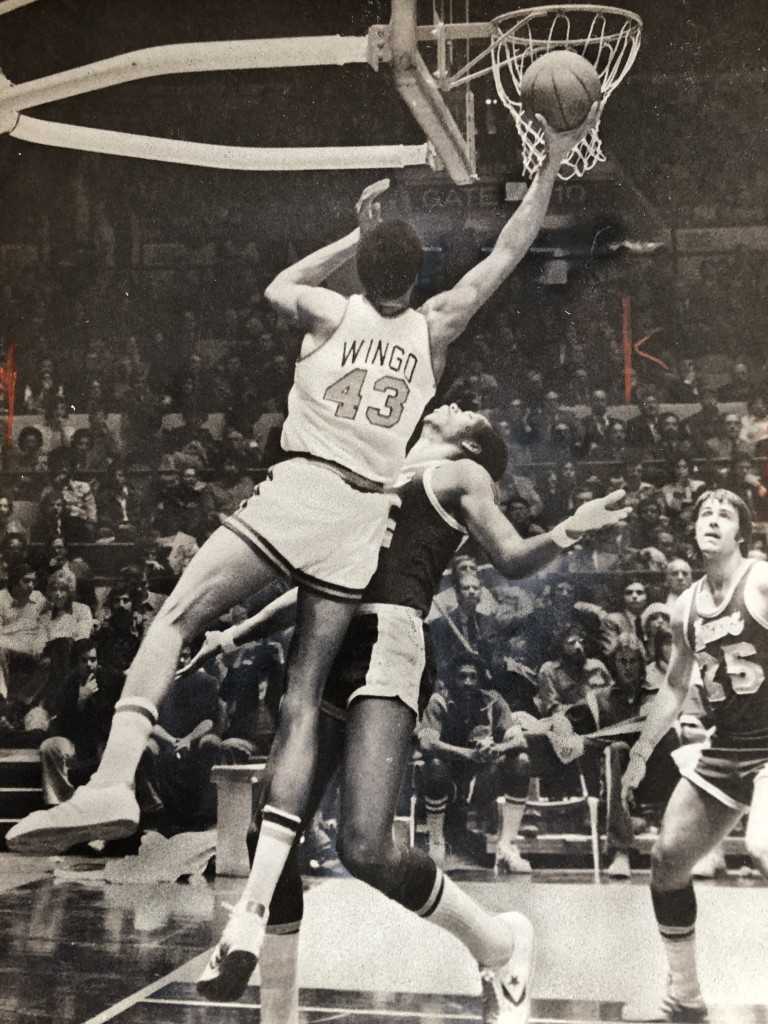

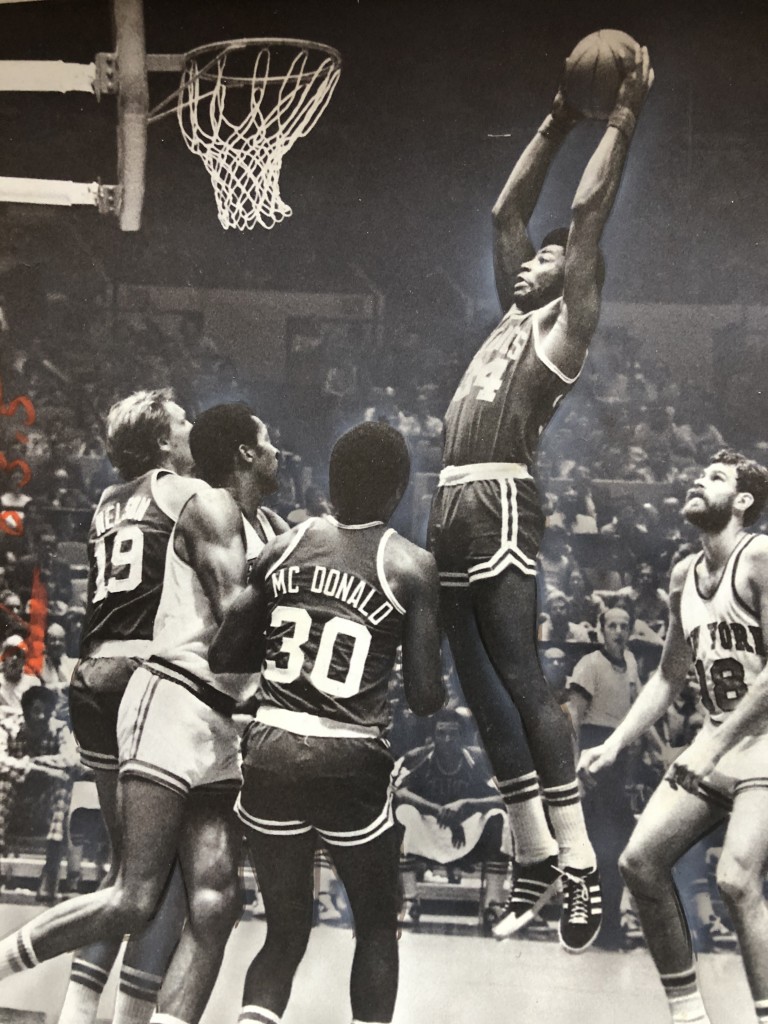

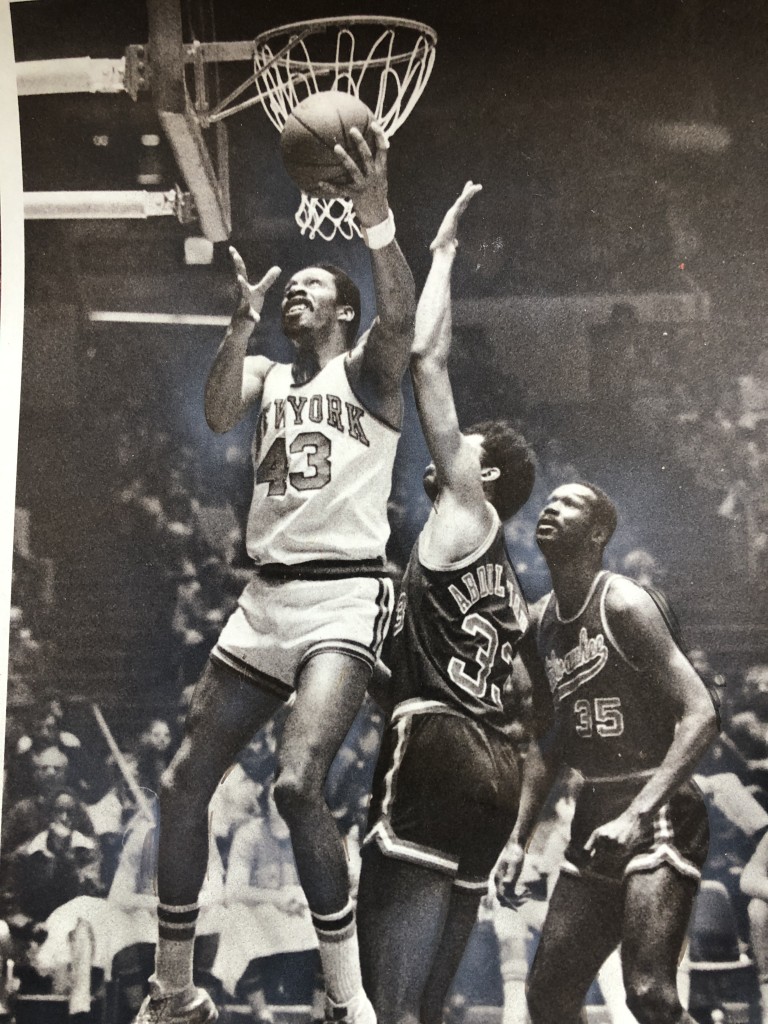

HARTHORNE WINGO

By Peter Vecsey

I covered the Knicks part-time for the New York Daily News when the unheralded but hardly unforgettable Harthorne Wingo first joined the team in 1972. He had played for New York’s unofficial Eastern League affiliate, the Allentown Jets previously after being ‘discovered’ at Holcombe Rucker Park by Dave Stallworth. The majority of prominent Knicks broke a sweet summer sweat in Harlem in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s and Stallworth, later part payment to the Bullets for Earl Monroe, was one of them.

Thus, I was completely unacquainted with Wingo, who appeared on a bus out of nowhere (otherwise known as Tryon, North Carolina) or his capabilities in the summer of '72 when he competed against my Julius Erving-led fantasy team I organized and coached for six seasons (four titles; two dominated by Doc, two by Sam Worthen) beginning in ’71. I also played sometimes early on, usually at garbage time, but once for more than a half pitted against Earl Manigault.

A few teams, like Tiny Archibald's squad and Dean Meminger's outfit, were loaded with pros, collections of former college players, here a Globetrotter, there a Globetrotter. My team was stacked three deep with boldfaced names; most religiously showed up Saturday or Sunday, depending on the schedule. Still, every once and awhile, I'd feel the need to import out of town hit men (Chicago, naturally) to further increase our prohibitive favorite status.

One weekend, I shelled out money to fly in Bulls forward Bob Love. He stayed at my downtown apartment, and we drove up the RDR, onto the Harlem River Drive Sunday to Rucker Park and got off at 155th street & Eighth Avenue. At the time, the 6-6 'Butterbean' already was an NBA All Star (three times total), All-NBA Second Team (twice), and later made All-Defensive Team three straight ('74-76) seasons. The Bulls ultimately retired his No. 10 jersey; for some unreasonable reason, managing partner Jerry Reinsdorf resists retiring the uniform of Love’s leather-bound book end partner, Chet ‘The Jet’ Walker.

Love was salivating to show up and show out at Rucker. Bob McCullough, a brief Cincinnati Royals teammate of his when both were aspiring rookies, had spun mesmeric yarns about the insane outdoor atmosphere, the tournament’s outrageous talent--much of it anonymous outside Harlem--and the freaked out fans who found unimpeded sight lines on tree branches and on the edge of a school building when the overflow crowds spilled into the street and they were left with nowhere else to squat.

Both Love and McCullough, who had averaged 36 points for South Carolina's Benedict College, were high Royals draft choices. Both were also cut in training camp. Love later hooked up with the Bulls. McCullough returned to Harlem where he earned a bunch of Science degrees, continued to strut his stuff on the blacktop until his knees gave out, and became commissioner of the Harlem Professional League, aka the Rucker Tournament, after Holcombe Rucker died at 38 of cancer.

McCullough had hipped Love to everything Rucker. Exempting Wingo! Butterbean got a harsh taste of him that afternoon between the indistinguishable lines.

For the most part, players basically didn't guard anyone in particular at Rucker. The run-'n-stun pace was too hot 'n hectic to stick with visualized assignments. After the opening tip, players promptly learned to attack the ball carrier on the break, and still got burned above the basket.

Known for his head and shoulder fakes, Love compensated for his lack of lift with cunning and confidence.

At Rucker Park, that rarely paid off. Numerous times that day, Love found himself worn and worn out by Wingo, who could not be picked off or faked out. When Love, back to the basket, finally elevated, Wingo suffocated.

After receiving several resounding rejection notices, Love returned to a huddle convened by me, his speech impediment (long since conquered) was beyond his control.

"Bingo!, Ringo! Dingo! Who the f-f- fuck is this guy, Wingo!?”

*****

Would love to hear from retired players about their own pet superstitions while active, or rituals staged by teammates, opponents, referees, coaches, writers, trainers, cheerleaders or anyone associated with the game you think are worthwhile and sanitary enough to share.

While you’re compiling elongated lists on short pieces of paper, here are some of mine that came to mind:

Hubie Brown: he’d hold an object, could be anything, sheets of plays, a program, towel, discharge papers of conscientious objectors he was about to cut, in his hand the entire game.

Jerry West: he’d never sit in a seat when he was the GM of the Lakers and Grizzlies. Instead he could be spotted standing at a half-court exit, fidgeting fretfully. Many GMs adopted similar stand up routines.

Stan Albeck: he prohibited anyone on his team from getting a hair cut the day of the game.

Truck Robinson: during games he’d incessantly pull on his wristband.

David Greenwood: when he missed a shot, he’d adjust the tape on his finger as if it were responsible.

Larry Bird: he’d frequently wipe the bottom of his sneaker with either hand. Larry Legend only did two things exclusively with his right hand, write and eat.

Michael Cooper and Bob McAdoo: the strings on their shorts were always out dangling in front.

Dominique Wilkins: he always seemed to look over at the coach after doing something good. Or maybe that was his brother Gerald, I’m confused. Just as I’ve never been able to decipher l who Gerald’s son looks more like, his father or Anthony Mason.

Dennis Johnson: while on the free throw line, before shooting, he’d bounce the ball the number of years he’d been in the league.

Cedric Maxwell: he’d habitually visit the locker room before the national anthem.

Otis Birdsong: each time he’d visit the welfare line he’d pull on his knee brace.

Paul Westphal: time spent on the bench resulted in a towel being draped over his legs.

Bill Walton: he’d repeatedly re-tie his sneaker laces during games, whereas Chris Morris would repeatedly untie his on his bench.

Gene Shue: he’d walk backwards along the bench when making substitutions.

****

During the 1984 All-Star break, Connie Hawkins and I dined together in Denver. Although there was plenty of room downstairs where the masses were congregated, the maître d’ escorted us upstairs to a deserted area. “Is this where you put your mixed couples?” Hawkins wryly wondered.

An hour later it became evident Connie had nearly figured out the seating arrangement. As the room filled, we realized we were surrounded by gay couples. Connie leaned over and whispered, “I didn’t know you cared.”

*****

After playing at Louisville, and helping Denny Crum achieve the Final Four in 1972, Ron Thomas, a 6-6 serial air ball jump shooter, muscled and hustled for five seasons with the ABA Kentucky Colonels, one the ’75 championship.

Teammate Dan Issel calls Thomas an enforcer. Maybe so, but I never felt he was mean enough to merit such a confrontational badge. Not in a league bloated with brawlers and bullies who’d stomp a mud hole in your ass and walk it dry… for fun.

Safeguarding their team’s stars, or getting even with a cheap shot artist was a contemptible excuse by those bad-to-the-bone boys to impair and immobilize indiscriminately.

Maurice Lucas, John Brisker, Warren Jabali, Wendell Ladner, Rich Jones, maybe Tim Bassett, were excessively qualified intimidators. What most outsiders don’t know is that the two toughest ABA players of all time were Neil Johnson and Mel Bennett.

Lucas ran ten rows into the stands to distance himself from Bennett. Johnson beat up Jabali on the court, tried to get to him in the opponents’ locker room, and finished him off on the team bus.

Hubie Brown’s ’75-76 Colonels flaunted two bodyguards:

Lucas prosecuted trespassers and went after cursing coaches who directed their profanity and disrespect at him, something that began at Marquette when he’d exchange post game punches with Al McGuire.

Thomas’ full-length function was to protect Hubie from Lucas whose threats of violence were taken enormously serious.

While listening to Hubie’s color commentary, my mind cannot help but wander to the following Bluster Brown installment.

On February 4, 1983, I strolled into Boston Garden, the NBA’s all-time mangiest and most beloved building, and scaled its soiled stairs to courtside where bombastic union guys who change the floor after events would sideswipe visitors on their iron carts if given an a clear path opportunity, then spew smack if they missed.

On this particular night, such belligerence led to a hostility involving Hubie and an innocent bystander, me. Never the best of friends when he coached, we were USA Network colleagues that evening. As we left the locker room area ten minutes after the game, one of these sadistic hobos came rumbling around the corner on his tomblike toy and nearly took our toes off.

It wasn’t the play Brown had diagrammed. And he let the guy know about it in unbiblical terms, with typical Hubie histrionics.

He had no sooner gotten some nastiness off his chest, than three or four of the guy’s co-workers, one as aggressive and profane as the other, circled us. Like it or not, I had been chosen into the episode.

‘Inciteful’ as always, Hubie naturally refused to back down.

All I could think of was, “I can’t believe I’m going to get my ass kicked holding down Hubie.”

Where was Ron Thomas when Hubie (we) needed him?

Just then Rick Robey came around the curtains from the Celtics’ locker room area, and, fortuitously for us, intervened. Using his 7-story, 265-pound frame as a buffer, we rapidly retreated without losing too much face.