K.C. JONES

By Peter Vecsey

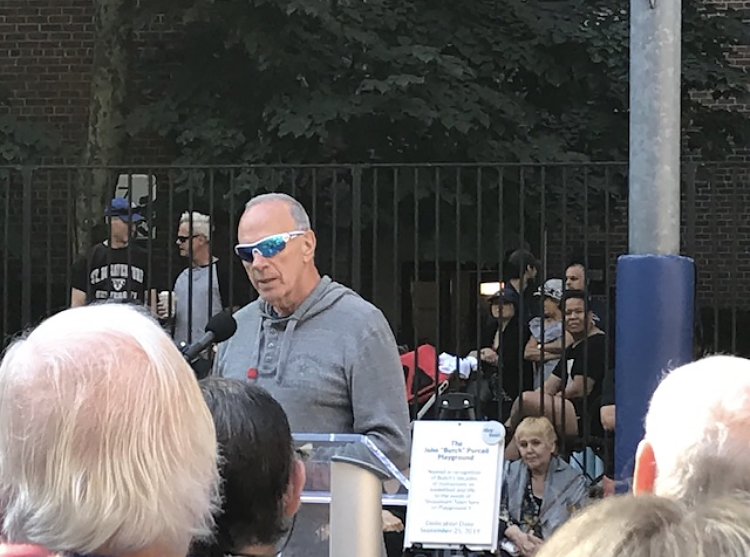

On September 25, 2019, John Purcell received the highest honor a street baller never imagines receiving. The outdoor courts he called home (familiarity with half moon baskets provided a distinct advantage over non- residents) would now bear his name.

Playground 9, near the First Avenue Loop, across the street from where he lived, became officially known as The John “Butch” Purcell Playground.

In 1968, Butch and his wife, Mary, became the sixth black family (I’d thought mine was the first) to break a hardcore racial barrier that existed since the Stuyvesant-Peter Cooper community—stretching from New York City’s 14thstreet to 23d, and First Ave to Avenue C--was built almost exclusively for returning white World War II servicemen.

An estimated 350 friends and neighbors, many whom ran the court early on with Butch and later matched basketball and baseball trivia wits with him, turned out to express their reverence.

I’d driven from Arizona explicitly to show ultimate respect for my co-coach of our deified Dr. J-Rucker Park team that won two out of four summer flings in the early-to-mid ‘70s.

I got to Long Island the day before, caught a 6 a.m. ferry from Shelter Island the next morning, and figured I’d have no problem making it on time for the 9 a.m. ceremony. But traffic was terrible. I panicked. Though alone, I veered into the HOV lane, and was pulled over almost immediately.

“I gotta hear this,” the policeman said sarcastically as I rolled down the passenger side front window. “What possible excuse do you have for pulling into the express lane with me in plain sight?”

I tried the truth.

Told him about driving back from Arizona (had the plates and the papers to prove, so far, no lies) to celebrate a playground being named after a friend of plus 50 years. Told him I was scheduled to speak and had to be on time. The risk of being ticketed overweighed the price in terms of license points and a stiff fine.

The policeman took my license and registration and went to his car. A couple minutes later, he was back at the open window. “I’m going to give you the benefit of the doubt,” he said, returning both. “Congratulate your friend for me.”

Eight paragraphs into today’s column, I’m finally ready to make my point, the same one numerous friends made to Butch during the weeks that followed the dedication; about 30 of us had thrown him a surprise tribute at Walt Frazier’s Restaurant months before that.

“Amazingly, you’ve been honored twice while you’re alive and still coherent. So many others are honored posthumously.”

Today is the first anniversary of Butch’s sudden death. I spoke to him the day before as he watched the NFL playoffs. He was 74.

*****

I can’t think of a more empty feeling than being honored posthumously. Family and friends may savor a belated salute to some degree, but who cares?! There’s only one appropriate time to acknowledge a person’s abundant accomplishments and that’s when they’re able to bask in the glory and enjoy the renown.

I felt strongly about that in 2014 when I was part of a Naismith Hall of Fame committee that voted for ABA candidates. George Gervin, David Thompson, Rick Barry, Hubie Brown, Bob Costas and the column’s staph writer, could have elected any number of players, coaches or executives. I pushed to pick Slick Leonard, 82 at the time, because he was in piss-poor health. Six years later, he’s still toasting his induction.

Conversely, K.C. Jones, 88, died Christmas Day following an unbearably long ordeal battling Alzheimer’s. Inducted into the HOF as a player in 1989, K.C. also warranted enshrinement as a coach while capable of comprehending the standing ovations were directed at him. By any scale and statistic known to voters, he deserve should’ve been the fifth to double dip, joining John Wooden, Bill Sharman, Lenny Wilkens and Tommy Heinsohn.

Has anyone ever demanded an explanation from HOF czar Jerry Colangelo why K.C. isn’t in Springfield as a coach? Has Jones ever so much as been nominated to the point where the Hall’s initial 9-member committee votes on him?

If so, has he ever reached the final plateau, which I’m informed now consists of seven anonymous electors as opposed to 24, the number for decades?

If not, pray tell me what could possibly be the rationale?

Before concentrating entirely on K.C. Jones as a coach, who reading this realizes he’s the owner of more championship rings (a daunting dozen) than anyone in NBA history? That’s right; he flaunts one more than Bill Russell and Phil Jackson, 11 with the Celtics (eight as a player), two as their head coach (‘84 & ’86), and two as an assistant, one with the Vitamin C’s in ’81, and one as a Laker in ’72.

Following that fabled season in Los Angeles under Bill Sharman whose Lakers conquered 33 straight opponents, still a league record, and captured the NBA championship, their first such success since relocating from Minneapolis in 1960, spanning seven consecutive calamities in The Finals, K.C. became the San Diego’s Conquistadors’ original head coach in August ‘72.

Pay strict attention now; after a losing season with the Q’s (30-54), K.C. never suffered another losing season, three with Washington, five with Boston and two with Seattle.

His Celtics’ teams attained The Finals four out of five seasons, the Bullets one out of three.

His NBA regular season career winning percentage was .674 (522-252). His playoff percentage was .587 (81-57).

Until 1996, when Pat Riley pulled even, K.C. was the lone coach in NBA history to win 60 or more games four times…yet never once won coach-of-the-year. The media determined award was inexcusably given to coaches with far inferior records. Prime examples are Phil Johnson (44-38) with the Kings in ’74-75, and Frank Layden (45-37) with the Jazz in ’83-84.

K.C. also was the lone coach to win 60 plus games with two different teams—Bullets and Celtics--until Riley did it with the Lakers and the Knicks.

Jones’ disdain for the voting process was registered May 14, 1986 in a Knight-Ridder article by Jere Longman.

“When Lenny Wilkens took over in Seattle (‘77-78) the Sonics were 5-17. They finished with the second best team in the league. He got one vote. It’s all politics.”

Warped judgments regarding how easy it is to coach top talented teams is much more responsible, I submit.

How often are we subjected to alleged experts of the round claiming anybody can coach superstars?

“You always hear stuff like, ‘My mother could coach the Celtics.’ Hey, why fight it? You can’t do anything about it,” K.C. sighed. “As long as we win games and the guys perform to their abilities, that’s enough reward.”

At the same time, candid coaches will own up in a jiffy it’s as hard to coach a great team as it is to coach a poor team. “The hard thing about coaching a great team is not over-coaching…” Dave Wohl stressed in the same article.

That requires the laid back personality of a coach comfortable with himself. K.C. Jones’ sphere, in other words. “He doesn’t try to force his ego on the players,” Larry Bird praised in an ancient Hoop du Jour column. “We already have enough egos around here.”

K.C. was a master of managing egos, impeccably illustrated by the manner in which he dealt with Dennis Johnson, whom the Celtics had acquired from the Suns for Rick Robey.

Decades later, Bird revealed his initial reaction: “We heard what people said about D.J. in Seattle (Wilkens branded him a cancer a couple seasons after he’d won Finals MVP when the Sonics won the ’79 titles).

“We heard there was friction (with coach John MacLeod concerning D.J.’s practice habits) in Phoenix.

“We heard he was difficult to get along with. Heard he was moody. So when we made the deal, I wondered how he’d fit in with us. But I figured if he couldn’t get along with K.C. Jones, he must really an asshole.”

D.J.’s bad practice habits continued to be a coaching challenge as a Celtic, but were counterbalanced by his demonic defense when the score was kept. Already a 4-time All NBA First Team defender upon arrival, he added two more in that category with Boston, and made All Second Team another three times.

The situation was win-win for player and coach. D.J. found himself idyllically relocated under the auspices of a man whose college, Olympic and NBA playing days were spent alongside revolutionary rim protector, Bill Russell. The same man--pay strict attention now—who was frequently given scrimmages off by Red Auerbach.

D.J. (like Russell) wouldn’t want to practice the day after playing a lot of minutes, Bird said. “When we wanted to run hard, K.C. would isolate him, tell him to take a seat on the stage. Otherwise, he would’ve disrupted practice. D.J. would be laughing, thinking he got over on us. But we were a step ahead of him.”

Call it superior, egoless, winning! Which is what K.C. Jones was all about his whole life as a player, a coach and a person!

Shamefully, such a realization never dawned on Jerry Colangelo and the anonymous acolyte Hall of Fame voters—and still may not—while K.C. Jones would’ve been around to appreciate the accolades.

I’m publicly putting them on notice not to be that erroneously egregious in the future.