PAUL WESTPHAL

By Peter Vecsey

To laugh often and much;

To win the respect of intelligent people

And the affection of children;

To earn the appreciation of honest critics

And endure the betrayal of false friends;

To appreciate beauty;

To find the best in others;

To leave the world a bit better

Whether by a healthy child

A garden patch

Or a redeemed social condition;

To know even one life has breathed easier

Because you have lived.

This is to have succeeded.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

(1803-1882)

Paul Westphal’s astonishing dismissal as Suns’ coach 33 games (14-19) into the injury-pockmarked 1995-96 season was unreasonable to all, exempting decision makers, Jerry Colangelo and Cotton Fitzsimmons. His previous three ascendant productions had resulted in 177 regular season victories (59 average), 25 playoff wins and five series successes, bejeweled by an introductory excursion to The Finals in 1993 versus the Bulls that dissolved in six games.

Abruptly!

Less than one minute away from defying the defending champions to beat them in Game 7 before their howling homers, the Suns’ 4-point lead was halved when Michael Jordan appropriated a Frankie Johnson aborted jumper, weaved the length of the court, and logged a strikingly uncontested layup-line-like basket.

“Wasn’t anybody ever taught to stop the dribbler?” I couldn’t resist texting Westphal upon seeing the replay of Jordan’s unruffled jaunt in ‘The Last Dance’ May 4, 2020. He had to be watching, I figured.

Correctly!

“Sigh,” he responded.

Almost instantly!

In real time, that ill-fated evening, Westphal had jerked backwards on the bench and manifestly moaned.

On the Suns’ ensuing possession, Scottie Pippen caught Dan Majerle’s short-armed corner catastrophe. Down two, the Bulls had the ball with 14.1 seconds left. During the time out Westphal was heard commanding that Jordan, and everyone else, be stopped from penetrating.

Jordan inbounded to B.J. Armstrong from the end line who rapidly returned to sender. The ball crossed midcourt in three seconds. Suffocated, Jordan passed to Pippen who promptly passed to Horace Grant. Though covered, Grant was within ten feet of attempting to tie matters. He never so much as gave the basket a shooting glance. John Paxson was by his lonesome above the 3-point equator. Grant found him for the flushed finish.

Years later, the summer of 1994, to be exact, during my exclusive interview with Jordan in his Orlando hotel room following his Birmingham team’s baseball game, Michael mocked Grant’s hot potato moment. “Horace always complained about not getting enough shots and then passed up a chippie.”

Not surprisingly, Jordan conveniently failed to give Grant credit for stripping a driving Kevin Johnson on the Suns’ last second gasp.

Westphal’s soaring credit rating lasted a whole two seasons, fertile ones, I again stress, before being appallingly discarded after several essential players had the audacity to get hurt.

Nobody hurt more than Westphal. He’d been guaranteed security. Fitzsimmons promised he was not in job jeopardy and swore, contrary to faint rumors, he had no intention to replace the 4-year assistant he chose to succeed him on the sidelines.

Westphal contended Cotton’s coaching ensembles had been taken out of the closet and dry cleaned in anticipation of his hostile takeover.

Fitzsimmons, an all-time favored friend, finished 40-42; but lost in the first round of the playoffs to the Sonics, three games to two.

FYI: It took the Suns until 1999 to win a series, beating the Spurs, 3-1. Prior to that, they’d been eliminated four straight times in the opening chamber, and captured a grand total of one series victory over eight seasons, coached by Cotton, Danny Ainge, Scott Skiles and Frankie Johnson.

Westphal felt so bitterly betrayed he abandoned Arizona—returning to his home state of California--and severed relations with a Suns organization…a franchise he exceled for five straight Hall of Fame seasons (‘75-‘80), averaging 22 points and earning First Team All-League three times and Second Team once.

Paul Westphal was the Phoenix Suns!

Knowing how much I loved the area, he offered me sweet deals on his home in Paradise Valley, as well as one of the last, if not the last vacant lot on the Marriott Camelback Inn golf course. I already had a holy home on Long Island. But shame on me for not concocting a plan to buy the lot. It sold for 500G. A house was built on it within a year and sold for $4 million.

Naturally, we stayed very much in touch over the years, closer, of course, when he coached the Sonics and Kings. Both jobs presented insurmountable problems—Gary Payton and Vin Baker in Seattle, and DeMarcus Cousins in Sacramento.

Westphal knew he was in acute trouble the first time he met in private with Baker. Vin vowed there would be no reoccurrences of previous incidents. He pledged allegiance to his new coach. Then broke down weeping.

Paul went home that day and told his wife, Cindy, this would be a short tour of duty. “When you look up power forward in a basketball dictionary, I doubt there’s a photo of one crying.”

Still, Payton proved to be far more difficult to deal with than Baker, Westphal told me long after being terminated following two seasons and 15 (66-61) games. He often showed up late for practice, disrupted it frequently by playing half-assed, provided backtalk from the backcourt on a regular basis, and persistently presided over Disorder on and off the Court.

“How Gary says things in the parameters of his personality is not always going to remind you of Henry Kissinger,” Westphal wryly noted in Hoop du Jour in mid-madness. “But, we wouldn’t trade him for Henry Kissinger, either.”

In mid-January 2019, I drove from New York to Phoenix with my dog, Oliver Twisted. The notion was to rent for several months, get to know the present-day Suns, dine with Legends-turned-TV commentators (Dominique Wilkins and Walt Frazier, for example) when they came into town with their teams, and very possibly bed down for the duration.

Revitalizing my relationship with Westphal, who’d returned to North Scottsdale for winters not all that long before, was something I looked forward to doing more than any of the above.

Soon after arriving, I received the following text from Westphal, who had no idea I was in Phoenix.

“If you get this, thanks for all your HOF mentions over the years. Looks more possible than ever now. Best regards, Paul.”

I apprised Westphal of my situation and asked about dinner and a Suns game. Because he was away for a couple weeks, we didn’t meet until Feb. 21. He chose the Texaz Grill, where he pigged out once a week, he confessed, to compensate for eating wholesomely the rest of the week.

“The place is OK if you don’t mind comfort food. If you want something healthier we can pick a different spot.”

Westphal also elected to eyeball a game involving Grand Canyon University, coached by him to the ‘88 NAIA title. Majerle was now its coach. When Dan spotted us walk in, he greeted me with a Thunderous handshake and shit-eating smile. The last time I’d seen him was years before at his restaurant nearby the Suns’ arena; he and radio analyst, Tiny Tim Kempton, sprung, sorta, from our table to break up a brawl.

As I learned at our pre-game meal, Colangelo maintains a forceful connection with GCU, and had advocated Majerle for the position after the Suns bizarrely bypassed their ultra popular assistant for the head job vacancy. I’m not even sure he was granted an interview.

Westphal told me he’d reconciled with Colangelo. The truce paved a friction free relocation to North Scottsdale.

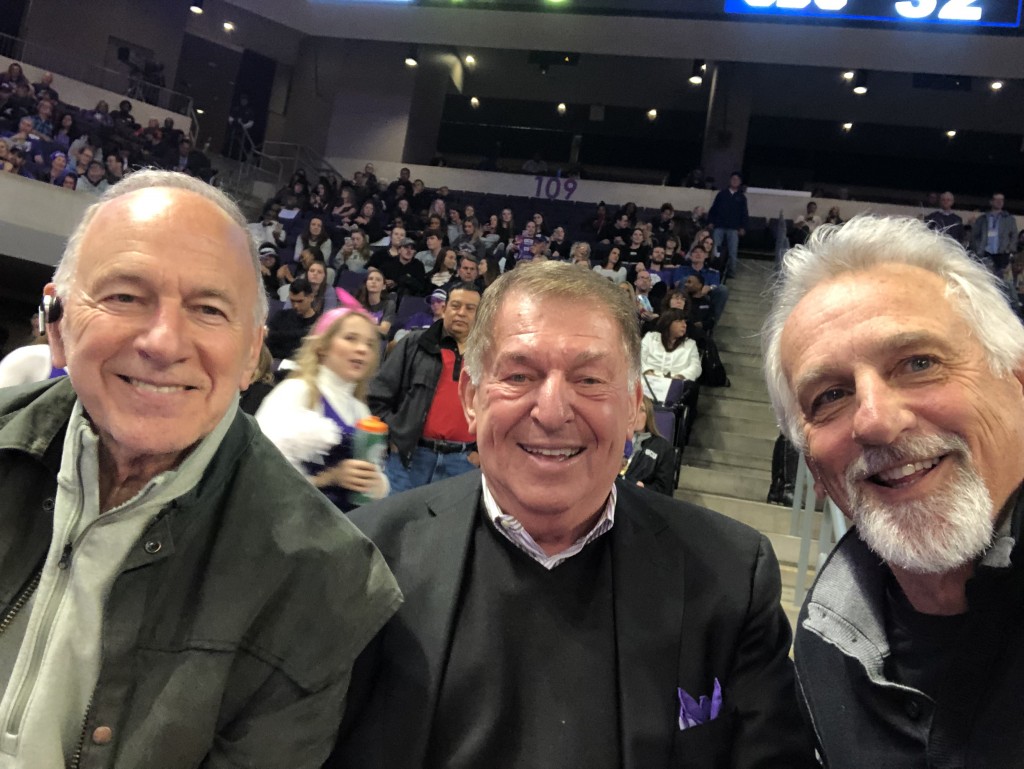

Having informed Westphal I was pissed off at Colangelo for too many reasons to explain here, he impishly asked during halftime intermission if I wanted to accompany him to see Jerry at his half-court seat.

A few minutes later, I look up and Colangelo is standing in front of me. “Paul tells me you don’t want to see me because I’m angry at you.”

“Paul’s got it wrong. I’m angry at you.”

Next thing I know, Colangelo is sitting alongside me and we’re making small talk, laughing for no good reason about who knows what, and participating in a photo shoot. At one point, Jerry wondered if I’d be interested in teaching a Sports Journalism course at GCU. I was. So he took out a little pad and diligently jotted down my pertinent information. The call from a school official has yet to come.

The game was lots of fun. Additionally, the college kids in the stands staged extremely entertaining rhythmic shows throughout. The evening’s highlight, however, was hanging on Westphal’s every word; absorbing his stories as an active player, coach, peripheral observer and astute analyst of today’s strategies and rules vs our younger days when everything was infinitely better, if no other reason than we were younger.

I wondered why Tommy Heinsohn didn’t give him more minutes subbing for JoJo White and Don Chaney the three seasons he played for the Celtics. Apparently, it was because he wasn’t deemed fast enough by Heinsohn to run an accelerated break. Hence, the Celtics’ motive for trading Westphal to Phoenix for Charlie Scott, advertised as speedier than amphetamines.

“I couldn’t guard JoJo in practice,” Westphal volunteered. “Nobody I ever went up against was quicker than JoJo. I just couldn’t do anything with him.”

Meanwhile, Westphal stole the ball from JoJo in the closing seconds of regulation in Game 5 of Boston’s epic triple overtime win in the ‘76 Finals…stole it, got fouled and completed 3-point play that tied the score at 94. In OT, he also made a crucial theft at John Havlicek’s expense with mere seconds to go to give Phoenix a 1-point lead.

On June 15, 2004, The Finals opener between the Lakers and Pistons was held in Los Angeles. Rather than scrutinize the game on site, I flew to Phoenix to watch it at the home of JoAnn and Cotton, who’d been diagnosed months before with lung cancer. Nurses told him he was the first person ever to show up early at the hospital for chemotherapy.

Good food was delivered. The conversation was upbeat. The fact we hardly looked at the TV did not prevent me in any way from imparting expert testimony about Game 1 in my next column. Before the month was out, he’s suffered a critical setback.

By then, the Pistons had been crowned champs and Dwight Howard was selected No. 1 by the Orlando Magic. In early July, I flew from New York to Phoenix to be close to Cotton in his final days, which turned into weeks. As ghastly as his condition was, his remarkably strong heart obstinately refused to stop beating.

Each day a new group of visitors representing every component of basketball, rushing in from surrounding states by the caravan. And each would get the okay to file into Fitzsimmons’ bedroom, monitored by JoAnn and nurse Georgia Johnson, Kevin’s mother, to voice quivering goodbyes.

I stood frozen at the top of the bed, powerless to reach out and touch Cotton. I thanked him for his friendship and expressed my love for him. He dimly nodded recognition.

On July 23, Fitzsimmons unmistakably was approaching death. Charles Barkley made a command decision and called Westphal in Southern California. “He told me I should hurry here before it’s too late,” Paul recounted at dinner. “I believe I was the last allowed inside his room to see him alive.”

Cotton was comatose when Westphal arrived on the 24th. His left hand was limp. Paul knelt beside the bed and held it. “I prayed for him not to be afraid, that his pain was ending, that he’d soon be with Jesus.”

Paul then told Cotton “I forgive you.”

Cotton softly squeezed Paul’s hand.

Westphal got exceptionally emotional reliving that vision. “It was the most impactful moment of my life.”

*****

Westphal died Jan. 2 from brain cancer. I urge anyone who hasn’t heard his Hall of Fame speech to do so on YouTube.

“What’s better than a person rooted in humility and gratefulness?!” writes Maureen Andariese, who placed Emerson’s above essay on a mass card for John, her husband-broadcaster when he died four years ago.

“The essay is about a person like Paul (John). He no doubt got ‘it’. I love when any human being can ultimately have the pleasure of arriving at the doorstep of truth and understanding about what is important in life, what matters most, what we’re here for. Whatever the question, love is the answer.

“God rest Paul’s beautiful soul and may his family find comfort and peace in every happy memory of him.”